Vitamin D Researchers

Vitamin Pioneers

A succession of 20th-century Wisconsin scientists made a lasting influence on our daily diets — and just how the foods we eat contribute to human health.

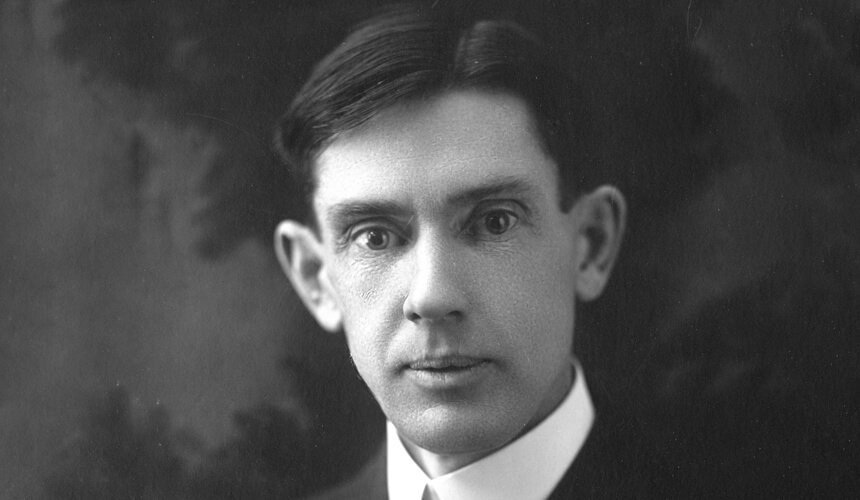

In the early part of the century, E.V. McCollum and Marguerite Davis BS 1926 kicked off decades of UW research that has demonstrated the connection between dietary deficiencies and disease. Using a rat colony for nutrition studies for the first time, McCollum and Davis — who worked with McCollum for six years, five of them unpaid — identified certain substances in specific foods that ensured normal growth. In time, although McCollum wasn’t a fan of the names, the substances were called vitamins A and B. He also laid essential groundwork for the discovery of vitamin D by finding that cod liver oil helped the rats avoid rickets.

Passionate about good nutrition, McCollum gained a national reputation by writing for McCall’s magazine. Dubbed “Dr. Vitamin” by Time, he offered this advice: “Eat what you want after you have eaten what you should.” He encouraged adding more milk products to the American diet, much to the delight of Wisconsin dairy farmers.

From The Park

In 1913, UW researchers E. V. McCollum and Marguerite Davis BS 1926 discovered the first vitamin, vitamin A, and in 1916, vitamin B. Harry Steenbock BS 1908 MS 1910 PhD 1916 discovered how to irradiate foods to enrich them with vitamin D. Conrad Elvehjem BS 1923 MS 1924 PhD 1927 discovered that niacin prevents pellagra. The UW’s involvement with vitamin research has continued with scientists such as Hector DeLuca MS 1953 PhD 1955.

Conrad Elvehjem BS 1923, MS 1924, PhD 1927 was next in line to contribute to the nutritional sciences by identifying nicotinic acid or niacin, now known as vitamin B3, leading to a cure for pellagra. A humble man and a quick study, Elvehjem served as university president for four years.

When McCollum left Wisconsin for Johns Hopkins, one of his graduate students, Harry Steenbock BS 1908, MS 1910, PhD 1916, continued with his own experiments. He discovered that he could increase the presence of vitamin D in foods by irradiating them with ultraviolet light — and grateful children could be spared from drinking nasty-tasting cod-liver oil. What happened next was remarkably selfless: eager to fortify its breakfast cereals, Quaker Oats offered Steenbock nearly $1 million for the rights to his findings, but he declined. Believing that the university should benefit from his work, he and eight other alumni started the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation and licensed his technology, earning the UW $17 million in the first ten years.

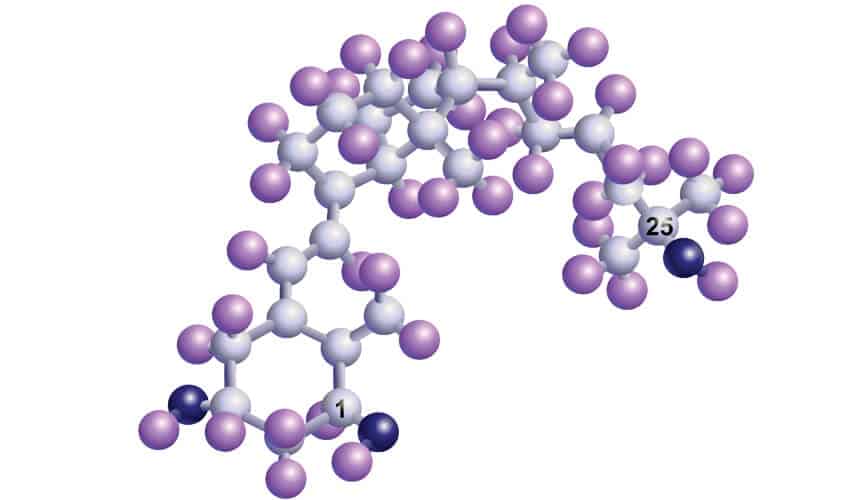

Steenbock’s final graduate student, Hector DeLuca MS 1953, PhD 1955, continued his work, making several key discoveries related to vitamin D. He then built analogs, compounds similar to the vitamin that treat a wide variety of conditions. He has filed hundreds of patents that have earned more than $500 million in royalties.

Little did McCollum know that the work he initiated more than a century ago would evolve into a new generation of UW scientists who continue to study nutrition and forge pathways to improving human health.

35° F

35° F