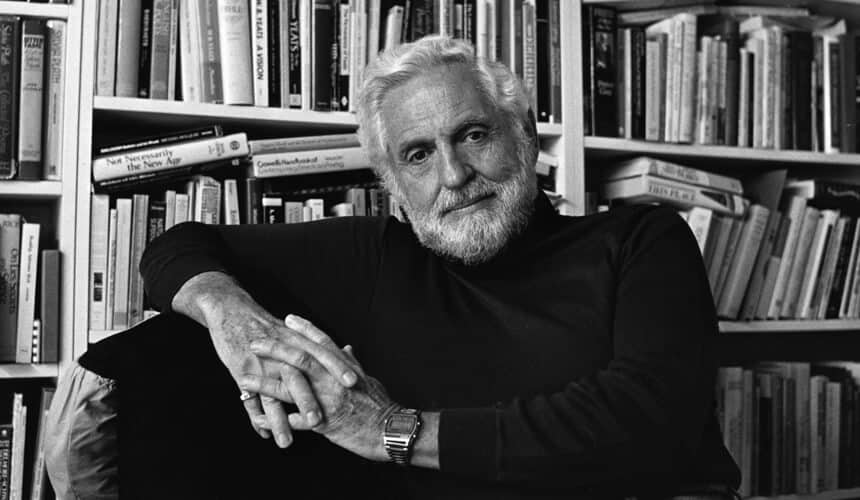

Carl Djerassi

Modern-Day Renaissance Man

ACT I

Carl Djerassi PhD1945’s story opens dramatically. Born to Jewish parents in Vienna, he split his childhood between his mother’s Austria and his father’s Bulgaria. When the Nazis annexed Austria to Germany in 1938, he and his mother fled, eventually landing in New York City with little money.

Djerassi raced through his education, obtaining his doctorate from the UW in 1945 at age 21. His dissertation studied how to transform testosterone into the female hormone estradiol, and that early interest in changing human hormones via chemistry would become the major theme of his scientific career.

He then moved to New Jersey, where he developed Pyribenzamine, one of the first commercial antihistamines. Shortly afterward, he relocated to Mexico City to become a researcher at Syntex, a then-little-known pharmaceutical company that was attempting to synthesize steroids from yams. With his team, Djerassi developed a steroidal progestin that ultimately became an integral part of the first oral birth-control pill.

Djerassi was recruited to Stanford in 1959 by William Johnson, one of his former UW professors. In addition to his chemistry research, Djerassi also worked with computer programmers on an early artificial intelligence project and started a non-toxic pest-control company that tweaked insect hormones to prevent their reproduction. He ultimately published more than 1,200 scientific papers, and he was well known at Stanford for championing diversity and mentoring younger colleagues.

ACT II

Djerassi’s daughter was a poet and painter, and after she died in the early 1980s, he converted his cattle ranch in Woodside, California, into the Djerassi Resident Artists Program. It’s now one of the largest arts-residency programs in the western United States, serving around 90 artists each year.

Djerassi didn’t try his own hand at creative writing, though, until another personal tragedy struck. His partner, literary scholar Diane Middlebrook, left him in 1983, and he took solace in a notebook. “My desire for revenge turned into an outpouring of poems — confessional, self-pitying, even narcissistic,” Djerassi said. He also wrote a novel and showed it to Middlebrook, who hated it. Djerassi promised he’d never publish it if they got married. They did.

Over the next 30 years, Djerassi’s literary writing grew more refined. He published five novels, five nonfiction books, several plays, and dozens of poems. He coined the term “science in fiction” to describe his interest in portraying scientists and academic topics in fictional contexts.

“You can become an intellectual smuggler by packaging the truth in a fictional context,” Djerassi said. “If it’s exciting enough, [readers will] learn something.”

Listen to Djerassi read some of his work.

EPILOGUE

Djerassi eventually returned to his heartbreak poems, producing a bilingual English and German chapbook called The Diary of Pique that was published by the University of Wisconsin Press in 2012. It was one of his last projects. Djerassi died of complications from cancer in 2015 at age 92.

Excerpt from “The Clock Runs Backward”

By Carl Djerassi

At his sixtieth birthday party,

Surrounded by wife, children, and friends,

The man who has everything

Opens his gifts.

Among paperweights, cigars,

Books, silver cases,

Cut glass vases,

Appears a clock

Made by KOOL Designs

In a limited edition.

A clock running backward.

A clock called LOOK.

Amusing.

Just the gift.

For the man who has everything.

How Faustian, thought the friend,

Soon to turn sixty himself.

What if it really measured time?

As the hands reached fifty,

He stopped them.

Books, hundreds of papers, dozens of honors.

Not bad, he thought: I like this clock.

But fifty was also the time

His marriage had turned sour.

He let the clock run on.

Forty-eight years, forty-five years,

Then forty-one.

Ah yes, the years of collecting:

Paintings, sculptures, and women.

Especially women.

But wasn’t that the time

His loneliness had first begun?

Or was it earlier?

Why else would one collect,

Except to fill a void?

Don’t hold the hands!

The thirties were best:

Burst of work. Success. Recognition.

Professor in first-rank University.

Birth of his son — now his only survivor.

What about twenty-eight?

Ah yes — he nearly forgot.

The year of THE PILL.

The pill that changed the world.

No — too pretentious, too self-important.

But he did change the life of millions,

Millions of women taking his pill, he thought.

The clock still regresses.

Twenty-seven years:

First-time father, of a daughter,

In time, his only confessor.

Now dead. Killed herself.

The beginning of his second marriage.

The first undone.

Early stigmata of success to come.

The doctorate not yet twenty-two.

The Bachelor of Arts not yet nineteen.

And the fallacy of presumed maturity:

First-time groom not yet twenty.

Backward: Europe. War.

Hitler. Vienna.

Childhood.

Stop. Stop. STOP!

–From A Diary of Pique, 1983-1984

40° F

40° F