Lake Mendota

The Most Studied Lake in the World

While you read: Listen to a song by UW limnologist Paul Hanson (PhD 2003), inspired by his research on Lake Mendota’s algae blooms.

Mendota is a French misinterpretation of a Dakota word (Mdo-Te) that means “the confluence or meeting of waters.” As perhaps the most studied lake in the world, Lake Mendota is a confluence not only of waters but of minds. At the meeting place of the Yahara Watershed, a network of scientists came together and founded the field of limnology, the study of inland waterways.

The first research paper about Lake Mendota was published in 1895 and titled “Plankton Studies on Lake Mendota: The Vertical Distribution of the Pelagic Crustacea during July 1894.” The dry headline belies the significance of the work: for the first time, researchers observed that a lake is made up of layers, and that the composition of plants and animals in those layers varies over the course of the year as lake temperatures change.

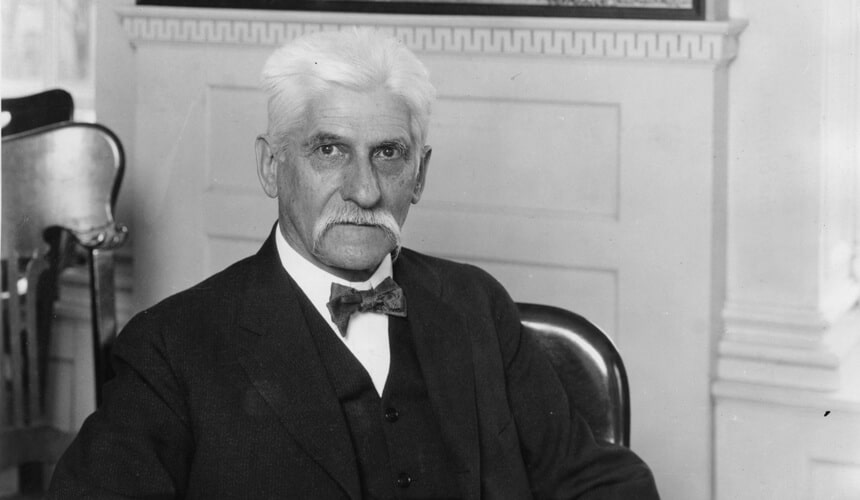

This simple idea was a pioneering one. The primary investigator, Edward A. Birge, was a zoologist who had intended only to replicate a small Hungarian study on Cladocera, the tiny lake crustaceans that eat algae. “This story, which Mendota told me without my asking for it, was the revelation that sent me into limnology,” he said.

Shortly afterward, Birge founded the university’s limnology department, and in 1900, he hired Chancey Juday, a young scientist who would become Birge’s closest collaborator. Over the next 40 years, the pair produced almost 1,500 pages of research. An interdisciplinary enterprise from the beginning, limnology attracted biologists, chemists, mathematicians, and other researchers from across campus. Though most of their work was on Mendota, Birge and Juday also drove a Model T out to some of the state’s northern lakes, many of which were inaccessible by road. (Juday broke an axel the first time he attempted to off-road the car.) They eventually founded a research station on Trout Lake.

Female limnologists have played an important role from the field’s earliest days. Along with Juday in 1900, Birge hired and mentored Harriet “Hattie” Bell Merrill MS1893, a Milwaukee schoolteacher who was an expert on Daphnia, a genus under the order Cladocera. In the early 1900s, Merrill twice traveled by steamboat to Brazil, alone, to conduct fieldwork. At the time, such trips were essentially unheard of for women. Merrill’s research contributed substantially to a taxonomy of Cladocera.

Daphnia continue to serve as benchmarks of Lake Mendota’s health. In 2014, a water flea invaded the lake, and the algae-eating crustacean population crashed. As the water grew murkier, UW limnologists prepared for the worst. But in 2015, Daphnia numbers began to bounce back, albeit slowly. There’s now hope that limnology’s tiny, resilient mascot will survive to inspire yet another century of science on Lake Mendota.

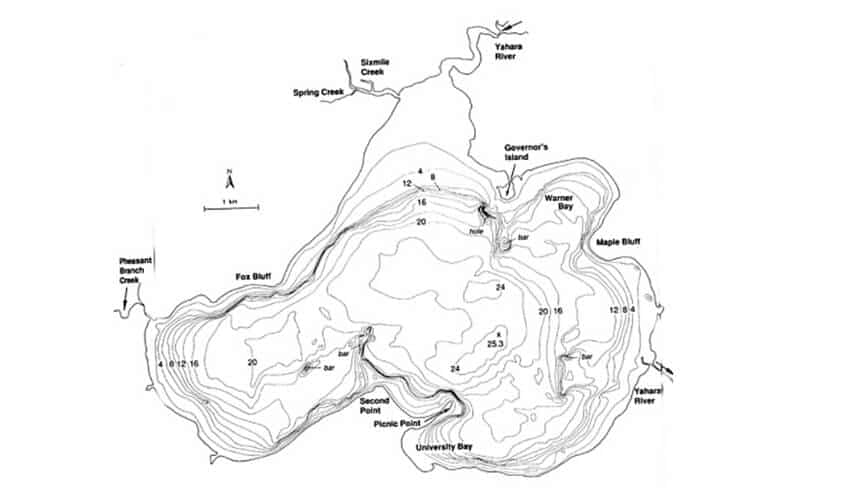

Lake Mendota Trivia Original names: Wonkshekhomikla, or “Where the Man Lies,” in

- Original names: Wonkshekhomikla, or “Where the Man Lies,” in Ho Chunk; Manto-ka, or “Snake-Maker,” in Potowatomi; Fourth Lake by early Wisconsin surveyorsMaximum depth: 83 feet

- Maximum depth: 83 feetSize: 9,781 acres

- Size: 9,781 acresNinth largest lake in Wisconsin

- Ninth largest lake in WisconsinMore than 60 species of fish have been reported in the lake

- More than 60 species of fish have been reported in the lakeMore than 12,500 academic papers and books have been written about Lake Mendota

- More than 12,500 academic papers and books have been written about Lake MendotaLake Mendota’s ice cover has been reported for more than 150 years; over this time, the average annual number of days it’s covered by ice has decreased by 29 days to just 35

- Lake Mendota’s ice cover has been reported for more than 150 years; over this time, the average annual number of days it’s covered by ice has decreased by 29 days to just 35

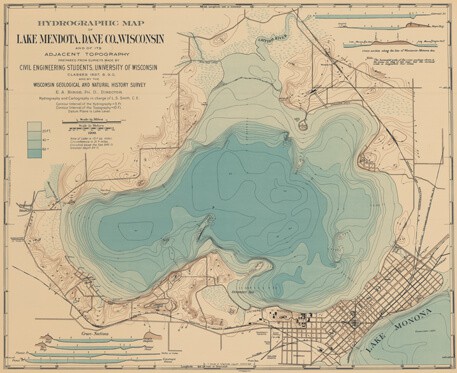

Historic hydrographic map of Lake Mendota. (Image courtesy of the UW Digital Collections Center.)

From Lake Mendota to Iguazu Falls: In pursuit of plankton

“I start Thursday for Asuncion and the Iguazu Falls. I have been told that no more than a half dozen white women have ever seen them. I can’t send my photographs from here but am getting a considerable amount of zoological material. We started out on horseback through dense foliage about 20 miles from the falls, whose roar from the cataracts echoed through the forest. Moisture spilled from every leaf end under an eerie green canopy and there was such a tangle of growth as to cause all forms of life to develop into eccentric forms in the struggle for survival. We continued on foot through barbed barricades of epiphytes and parasites. Underfoot, the Selaginella was equally precarious and I sunk in up to my boot-tops every step of the way. Some tree trunks with 6 in. thorns sticking out in bunches grabbed my clothing and by the time we got to a clearing, I felt I had awakened from a nightmare. At last we reached our destination.”

From the notebook of Harriet Bell Merrill (MS 1893), the first female limnologist at UW-Madison, during her 1902 fieldwork in Brazil.

68° F

68° F