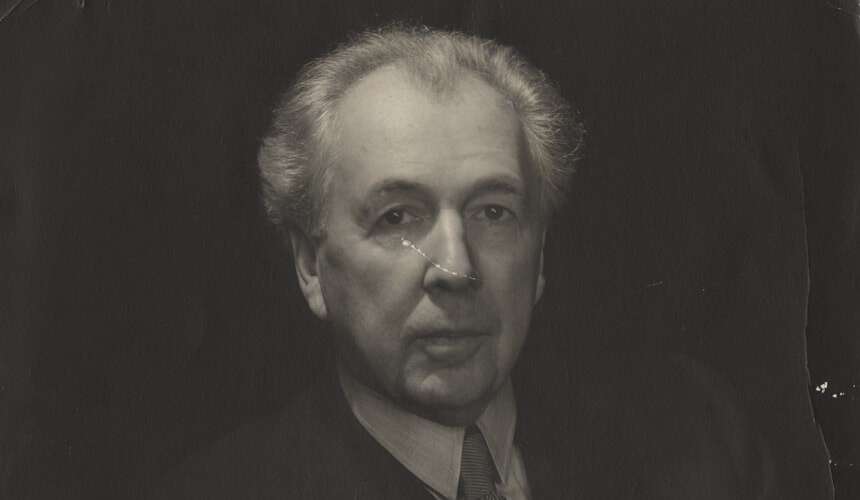

Frank Lloyd Wright

The 20th Century’s Architect

Although he soared to fame as the most acclaimed architect of 20th-century America, the design for Frank Lloyd Wright’s life always included Wisconsin.

Born in Richland Center in 1867, Wright enrolled at the University of Wisconsin as a special student in 1885, and he paid his way by serving as an assistant to an engineering professor. But by 1887, he had given in to the pull of big-city Chicago, taking work there as a draftsman. He finally earned a Wisconsin degree in fine arts, albeit an honorary one, in 1955.

Wright believed that America deserved its own building style, and he broke away from European influences to develop “organic architecture,” which allowed structures to exist effortlessly with nature. He envisioned clean, horizontal lines and continuous interior spaces that used materials of natural beauty, such as locally sourced wood and stone. “Organic architecture takes this thought from within the nature of the thing. It is a profound nature study,” he said.

Much of Wright’s early work focused on private residences, and in the 1930s, he designed Usonian houses for middle-class clients. Characteristic of the U.S., they were practical and affordable and didn’t require servants. He called upon these elegant, geometric principles when he was commissioned to design the Unitarian Meeting House in Madison in 1946.

As work lagged during the Great Depression, Wright reconnected with Wisconsin, creating Taliesin, an architectural school in Spring Green. His vision for Madison included a “dream civic center”; he drew the plans in 1938, but nearly 60 years would pass until the city constructed Monona Terrace.

Wright devoted his final 16 years to the Guggenheim Museum, a New York City landmark. Home to modern art, the building has a breathtaking design that echoes a gigantic seashell, taking visitors through its galleries via a central spiral ramp.

With more than 500 completed designs in his lifetime, Wright holds an undeniable place in American culture. He graced a two-cent postage stamp in the 1960s, and Simon and Garfunkel named him in a 1970 song. He was fully capable of influencing Americans’ “whole existence,” a 90-year-old Wright told television journalist Mike Wallace. The architect believed that when he created a beautiful space, it was “genuinely transformative … It would make the people different who inhabited that space,” says UW history professor William Cronon BA1976.

Staggeringly arrogant, undeniably brilliant, Wright left a tangible mark on the world. But he remained, at heart, a Wisconsin boy, saying, “I still feel myself as much a part of [the state] as the trees and the birds and bees are, and the red barns.”

60° F

60° F